The following text is very long and complex. We, ourselves, are not entirely satisfied with it yet and it is likely that it will be undergoing changes throughout our developing studies of Joan of Arc.

The material we have gathered and studied was to help us find out in which religious reality Joan was raised and prepared for her military mission and how religion was politically used to create and promote her story in the Middle Ages as well as in our own time. It can also help us establish her own religious personality or – to be more exact at this stage – what her own religious attitudes could have been like.

One of the main reasons why we are not yet satisfied with the emerging results of our study is that it is almost impossible to tell what Joan’s kind of religiosity really was. It is one of the factors which are almost taken for granted that she was exceptionally pious. But while there is indeed little doubt that she really was pious (especially by our standards today), we cannot, on the basis of the evidence available, tell if her piety was really far above the average of her time.

The text contains elements of Joan’s life (of which there is evidence), some which could have been existing in her experience, but also those which were certainly in her background education as they constituted part of religious and social reality in her days. All these elements form the unique atmosphere which can help us to understand her and her milieu better.

To enable readers to move quickly through the vast topic of this chapter, we have divided it into several topical sections which are:

Joan’s induction to religious life:

1. The Sacraments

2. The environment

Joan’s Saints

The role of virginity in Joan’s mission

The role of prophecy in medieval narrative

The role of religious imagination and practices in her story

Religious fasting

Theological justification, heresy and “theological correctness” (TC)

Joan as a visionary and a miracle worker?

Was Joan a tertiary?

Comparison with other medieval mystics

God stands by the side of the righteous”

Final remarks

Footnotes

Joan’s induction to religious life

Baptism those days took place between the 1st and 3rd day of life.

“The mother was unable to go [to Church – MM] because of her physical condition and because she was religiously unclean due to the flow of blood following birth. A group consisting of the midwife, the baptismal sponsors and perhaps the father went to the parish church.”

(Joseph H. Lynch. “The Medieval Church. A brief history”. London 1992, p. 276)

We now know the names of Jeanne’s parents and the names of her baptismal sponsors (godparents). We know – from Jeanne’s own words – the name of the priest who baptized her:

“Asked which priest baptized her, answered that she believed it was messire Jean Minet (“Jehan Nynet”). Asked whether the said Nynet was still alive, answered that yes, she believed”.

We do not know however who her midwife was. And it is somewhat surprising, since her name would have been easily remembered:

“In each little town in this region at that time, married women when one of them was pregnant, got together in the presence of a parish priest to elect a midwife who would inspire the greatest confidence. She took an oath before the priest, an oath conforming to an Episcopal law which demanded that the chosen woman assist at births in order to assure the health of the newborns’ souls if they were in danger of death, a reality which, sadly, happened all too often.

This election did not necessarily confer knowledge on the elected woman, since we know that the midwife habitually had at her side several matrons experienced in matters of birth. But her presence assured everyone in question. This custom perpetuated itself in Domrémy and its environs until the 19th century ended the local tradition. The last midwife elected from Goussaintcourt, a neighbour village to Domrémy-La-Pucelle, was Marguerite Etienne. She exercised her talents until 1888.” (Roger Senzig, Marcel Gay. “L’Affaire Jeanne d’Arc”. Editions Florent Massot, 2007, p. 53-54).

And yet we know nothing about Jeanne’s midwife, she herself mentioned quite a few of her godparents in 1431 but not her midwife.

But, returning to baptism, this is how in the Middle Ages the procedure of Baptism would have looked:

The priest would meet the whole group at the church door. He would then ask the child’s name and at that very moment the child would receive his/her name. Then the priest would exorcise the child in order to clean it of any evil spirits, thus giving the child officially the status of a catechumen (probationary status). Only then the whole group, headed by the clergyman, could enter the church to approach the baptismal font. After asking the child a few questions, answered by the sponsors with “I believe”, they would strip the child naked. The clergyman would then plunge the child three times in water, thus baptizing it “In the Name of the Father and The Son and The Holy Spirit”. Only sometimes sprinkling the child with water was used instead of plunging it in water.

What is interesting is that the child would then immediately receive his/her First Communion as well through a sip of wine. If the proceedings were presided over by a bishop, then the sacrament of Chrismation (Confirmation) followed as well which means that the child received all three sacraments at the same time.

Later the whole group retired, going either home or to a tavern, where gifts were given to the child and its mother.

We do not know when Jeanne received her Chrismation, whether on the same day or later as a teenager. We know however that she was receiving the Eucharist, but not very often. And we deduce this from her own testimony during her inquisitorial trial in Rouen (Isabelle Romee, her mother, said on 7 November 1455 that Jeanne was receiving Communion every month, having gone to confession).

During her second public interrogation on 22 February 1431 (1430 according to the old calendar) Jeanne was asked if she was receiving the Eucharist during any feast other than Easter. She replied by saying “Passez outré” i.e.“Pass on” (In the Latin version a longer phrase is inserted: “dixit interroganti quod ipse transiret ultra” – “asked the interrogator to go to next questions” page 38) and started talking about something completely different, namely about her “visions”.

An additional explanation we find in her words on 3rd March when she was asked whether, when she was going through the country with her army, she was receiving the Sacraments of Penance and the Eucharist often. “She responded that yes, sometimes” (“respondit quod sic, interdum” page 79). Asked then if she received the said Sacraments in man’s dress, she “stated that yes; but did not remember to have received them when armed” (“respondit quod sic; sed non recordatur quod reciperet in armis”).

From among the 70 articles of accusation read out to Jeanne during her trial, Article XV was exclusively about Sacraments and her… masculine dress. We are quoting this article in its entirety:

“Jeanne, having many times asked that she might be permitted to hear Mass, had been invited to quit the dress she now wears and to take again her woman’s dress; she had been allowed to hope that she will be admitted to hear Mass and to receive Communion, if she will renounce entirely the dress of a man and take that of a woman, to suit her sex; she had refused. In other words, she had chosen rather not to approach the Sacraments nor to assist in Divine Service, than to put aside her habit, pretending that this would displease God. In this appears her obstinacy, her hardness of heart, her lack of charity, her disobedience to the Church, and her contempt of Divine Sacraments” (page 187)

To this article “Jeanne responded that she would rather die than revoke what she had done by the order of Our Lord” (“respondit Johanna quod carius diligit mori quam revocare id quod ipsa fecit de praecepto domini nostri”).

This was later confirmed in Article 5 of the final 12 Articles of accusation. The questions addressed in the Article 15 were raised shortly before Easter (in that year it fell on 1 April, which, according to the old calendar, was the first day of the year 1431).

The Holy Communion was however, according to some witnesses, administered to her early in the morning of Wednesday 30 May 1431 shortly before the planned execution. Apparently Bishop Pierre Cauchon finally gave his permission.

If we had to start with the village of Domrémy where Jeanne grew up, we could well begin with its very name which supposedly means “Saint Remigius” or “Saint Remy”. In fact there are four villages with the name “Domrémy” in the area. The one we are discussing now has been renamed “Domrémy-La-Pucelle”. The Latin version of the name “Domrémy” is “Dominus Remi”, which means exactly “Master Remi” or “Lord Remi”(1). The village has a medieval church bearing the name of Saint Remy. This particular saint is also a patron saint of Reims, a city in whose cathedral the crowning and anointing of French kings took place. Both the village and the city remain important in Jeanne’s story. The village of Domrémy was, during the early centuries of the Middle Ages, within the zone of influence of the Abbey of Saint Remy of Reims…

“…From where it follows that every year, on the occasion of the patronal feast, Jeannette d’Arc heard the cure of the parish, Messire Guillaume Frontey, a native of Neufchateau, deliver a panegyric to the patron saint of the church and recount the great features of the baptism of Clovis, not as we read it in works by Gregory of Tours, but overloaded with wonderful additions like in a primitive version of Hincmar’s narrative”. (Simeon Luce.“Jeanne d’Arc a Domrémy. Recherches critiques de la mission de la Pucelle”. Paris, 1886, p. XXXIV)

It is usually assumed that the current church in Domrémy is the original church which Jeanne regularly visited and in which she was also baptized. This might however be a false assumption. Please refer to the link provided in the footnote (1). It explains why the current church could have been built after 1450 if not even later. By 1450 NOBODY from Jeanne’s family was living in Domrémy anymore: her brothers had moved to the area of Metz, her father had died before 1440 and his wife Isabeau Romée had moved shortly afterwards to Orleans. Inside the church there is an old, very simple baptismal font made of stone. Local tradition has it that it is the one at which Jeanne was baptized. But as the link shows, there is a marble plaque with an inscription explaining that it was previously in the chapel of John the Baptist. The chapel itself was in the “Castrum nominatur Insula” i.e. in the “castle named Island”, the famous “Chateau de l’Isle”, which the family of Arc leased, together with Jean Biget, from the family of “de Bourlemont”. It depends of course WHEN the font was transferred to the church. If it was after the birth of Jeanne, then it would rather be unlikely to be the one of Jeanne’s baptism. Of course, for this deliberation we are assuming that Jeanne’s own words about the place of her baptism (as she heard about it from her parents) are true…

It is usually assumed that the current church in Domrémy is the original church which Jeanne regularly visited and in which she was also baptized. This might however be a false assumption. Please refer to the link provided in the footnote (1). It explains why the current church could have been built after 1450 if not even later. By 1450 NOBODY from Jeanne’s family was living in Domrémy anymore: her brothers had moved to the area of Metz, her father had died before 1440 and his wife Isabeau Romée had moved shortly afterwards to Orleans. Inside the church there is an old, very simple baptismal font made of stone. Local tradition has it that it is the one at which Jeanne was baptized. But as the link shows, there is a marble plaque with an inscription explaining that it was previously in the chapel of John the Baptist. The chapel itself was in the “Castrum nominatur Insula” i.e. in the “castle named Island”, the famous “Chateau de l’Isle”, which the family of Arc leased, together with Jean Biget, from the family of “de Bourlemont”. It depends of course WHEN the font was transferred to the church. If it was after the birth of Jeanne, then it would rather be unlikely to be the one of Jeanne’s baptism. Of course, for this deliberation we are assuming that Jeanne’s own words about the place of her baptism (as she heard about it from her parents) are true…

The neighbouring villages of Greux, Bermont or Maxey, even Moncel also played their role in Jeanne’s early life. Greux was in fact the other part of Domrémy. These two villages had one parish church which was in Greux; the church in Domrémy was a filial church. The fact that it was Greux which had the parish church makes it safe to assume that Jeanne was visiting that church as well. Unfortunately the original church in Greux does not exist anymore. As we are informed by the local Researcher from France, the church was destroyed during the Thirty Years War (i.e. between 1618 and 1648). As it turns out, not only the new church is in a different place but the whole village of Greux. Please have a look at the aerial photo with information regarding locations.

In Bermont there was – and still is – a shrine of the Holy Virgin Mary. The old statue of the Virgin Mary with Child has been transferred to the St Joan’s basilica in Bois Chenu.

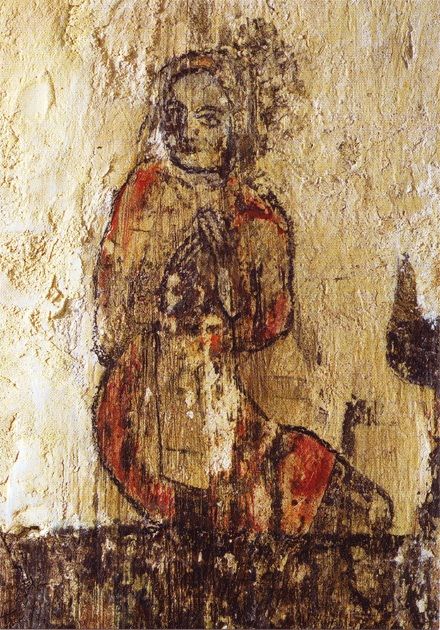

The shrine in Bermont is apparently the one which Jeanne visited regularly. Nowadays the chapel is dedicated to St Thebaud (Theobald). In 1998, during restoration works, a quitelarge number of 15 wall-paintings was found inside the chapel. Of these 15 only two are available for viewing. As we are informed, to our astonishment nobody can obtain access to the remaining images. One presumes the two images depict Jeanne d’Arc.

Her later “voices” Jeanne attributed to three saints: St Michael, St Catherine and St Margaret. And as it transpires, those saints she knew about since her early childhood: the chapel in Moncel was dedicated to St Michael, and the other two saints she had seen in the windows of the local churches: St Catherine in the window of the church in Domrémy and St Margaret in the window of the church in Maxey. There is still a statue of Saint Margaret in the church in Domremy, dating from the late fourteenth century.

The church in Maxey was dedicated to St Catherine and an old story tells us something more about the connection of the church to the saint. Some authors tell us about the story. So Marina Warner repeated the story after Vita Sackville-West, and she in turn repeated it after Simeon Luce. And Siméon Luce in his book (“Jeanne d’Arc a Domrémy. Recherches critiques de la mission de la Pucelle”. Paris, 1886, p. 19) quotes an entire document (on pages 16-21) which is nothing else and nothing less than a testament of one of the nobles from the family of de Bourlemont. Jean de Bourlemont (“Jehan de Boullaimmont”) wrote his testament between 3 and 23 October 1399. In it we find an interesting paragraph which in the old French reads as follows (translation below):

“Item, je veul que les aiandres de saincte Catheline de l’esglise de Marcey dessus dit soient rendues et restablies la dicte eglise pour priier pour mi, pour ce que messire Waulchierz, curetz jadis d’icelle esglise, les m’avoit données, ensemble aulcunes autres grosses aiandres qu’il avoit faites, si comme il disoit, et escriptes de sa main, et sont les dictes aiandres en Bourgogne en mon ecrin.”

The term “aiandres” which we show in bold lettering is very old and there are some doubts as to its meaning. It actually has several possible meanings, one of them being “relics”. Hence, after a consultation with our befriended Researcher of the story of Jeanne d’Arc in France, we decided to use it in this meaning:

“I wish that the relics of Saint Catherine, which were in the church of the afforementioned Marcey (Maxey), be given back and restored to the said church in order to pray for my soul, because Messire Waulchierz, once the priest of that church, had given them to me, with any other large relics that he had made, so as he said and wrote himself, and are the said relics in Burgundy in my jewellery box”.

Of course nobody has ever seen any “relics” of Saint Catherine as the saint herself is considered to have been only a mythical person, yet Jean de Bourlemont somehow believed that he had her relics in his possession. This is not surprising though as sales of relics, whether authentic or fake, were booming in the Middle Ages. And as it was a story from the year 1399, that is from the time shortly preceding Jeanne’s birth, we are quite sure it must have been well known to the locals – and to Jeanne herself – at the time she was around.

Saint Catherine later appears in the narrative of the story of Jeanne more often than any other saint.

The shrine of Notre Dame de Bermont was, as we pointed out already, also frequently visited by Jeanne. Jean Morel, a labourer from Greux, testified during the rehabilitation trial. On Wednesday the 28 January 1456 (1455) he said: “sometimes she even went to the church or chapel of Notre-Dame de Bermont, near the village of Domremy, while her parents believed her to be in the fields to plow or elsewhere.”

The same witness “also stated that, when she heard bells ringing for Mass and she was in the field, she came to the village church to hear mass, as the witness assured seeing.”

And also: “questioned, he said he saw Jeannette confess at Easter time and at other solemn feasts, he saw her confess to Messire Guillaume Fronté, then pastor of the parish church of Saint-Remy de Domrémy.”

Other witnesses expressed themselves similarly, for example Messire Dominique Jacob who was (at the time of the rehabilitation trial) the cure (i.e parish priest) of the church in Montier-sur-Saulx in the diocese of Toul, and who was “thirty five years or so”, added that as a child he had seen Jeanne kneel in the field when the church bells rang for service. And the church warden and bell-ringer from Domrémy, Perrin Le Drappier, testified that when he forgot to ring the bells, Jeanne scolded him and even promised to give him some gifts if he remembered to ring the bells on time.

On 22 February 1456 (1455) in his testimony Jean de Dunois, the same one in whose crypt Serguei Gorbenko found a skeleton which he claimed to be the one of Jeanne, went even further:

“Testified that she had a habit to go to church daily at the time of Vespers or towards evening; she had the bells rung for half-an-hour, and assembled the Mendicant Friars who were following the army. Then she began to pray and had an anthem in honor of the Blessed Virgin, Mother of God, sung by the Mendicant Friars”.

She also liked making offerings of candles to “her” saints, mainly to St Catherine. On 15th March 1431 (1430) she confirmed that she “never lit as many candles as she wished” to St Catherine and St Margaret.

Her favorite saint was Saint Catherine of Alexandria. The other two Saints, St. Margaret of Antioch and St Michael the Archangel, played a less important role in her story. (2) All three Saints had swords as some of their symbols. In the case of the two female martyr Saints they were swords of enemies, in the case of St Michael it was a sword which helps defeat evil and the enemy. Quite fitting from the point of view of what Jeanne was about to do… In Jeanne’s own coat of arms there was later to be one sword too…

The legendary Saint Catherine, who most likely never existed, was, according to the legend, seized and brought before the Emperor Maxentius and began to explain Christianity to him. Fifty learned men were summoned by the Emperor to debate her, but she confounded them all. Maxentius demanded then that she marry him, which she refused. Later a special machine with four wheels was invented to execute her but an angel destroyed it. In the end she was beheaded with a sword.

Saint Margaret was born again from the belly of a dragon. In one version of the legend, she enters a monastery dressed as a man. She can see the devil but her purity protects her against him. She refuses to marry Olybrius, the prefect of Pisidir and is thrown into prison by him. She miraculously endures martyrdom and by this succeeds in converting five thousand bystanders. In the end she is beheaded.

Some elements of both legends could later be compared with Jeanne’s story: Jeanne was also dressed like a man; whether she was herself a member of a religious order we will study in a moment. She was confronted by about sixty assessors and judges in Rouen and is widely believed to have been martyred as well. During her captivity she jumped off a tower in the Beaurevoir castle – and there is a story of St Margaret who, as a 15-year-old virgin, jumped off a high building to preserve her chastity. The story is however a later one and does not appear before the time of Joan of Arc…

There are also simple elements (perhaps coincidences, perhaps not…) which connect the Saints to the story of Jeanne but in a different way. So Catherine was the name of one of the sisters of Joan of Arc; it was also the name of a sister of Charles VII, the widow of Henry V of England; the widow of the Dauphin Louis, elder brother of Charles VII, was known as Marguerite de Bourgogne; Michelle was the name of the sister of Charles VII, wife of Philippe Le Bon. Let us add to it that St Michael was the patron saint of the French royal family of de Valois and that he was particularly venerated by Charles VII whose son, the next King, Louis XI founded the order of knighthood of St. Michael (on 1st August 1469).

“But Saint Catherine of Alexandria stood chiefly for independent thinking, courage, autonomy and culture. She was the saint chosen by young unmarried women in France. Saint Margaret of Antioch, though her spiritual sister in the paintings of the helpers was also her opposite number. Alexandria was the centre of classical allegorical studies, where the Bible, for instance, was read in the tradition of Philo Judaeus to uncover the secret meanings under the narrative surface. Antioch, the other great school of learning in the Byzantine Empire, was the seat of the literalist school, where mystical interpretations of the Alexandrians were shunned. Joan, therefore, unconsciously named her visions after the two poles of the Christian philosophical tradition.” (Marina Warner. “Joan of Arc. The Image of Female Heroism”. London 1981,p. 134, 135)

St Catherine might be a character formed on the historical (and non-Christian) Hypatia from Alexandria who was indeed murdered (by Christians) in the year 415 AD.

Marina Warner is inclined to consider Jeanne as “Neoplatonist in inclination” as she apparently saw “no incompatibility between the world of the spirit and the visible creation”. (3)

But having stressed the importance of particular saints to Jeanne, we have to remember that on occasions she was mentioning other saints as well, like the Archangel Gabriel or others. The Batard d’Orleans, Jean de Dunois, testified in 1456 about what she said to him in Orleans after a clash erupted as to the conduct of military operations:

“In God’s Name,” she then said, “the counsel of My Lord is safer and wiser than yours. You thought to deceive me, and it is yourselves who are deceived, for I bring you better succor than has ever come to any general or town whatsoever, the succor of the King of Heaven. This succor does not come from me, but from God Himself, Who, at the prayers of Saint Louis and Saint Charlemagne, has had compassion on the town of Orleans, and will not suffer the enemy to hold at the same time the Duke and his town!” (The Duke Charles of Orleans was then a prisoner in England.) (4)

The role of virginity in Joan’s mission

There is of course no direct proof that Joan was a virgin, as there is no proof of lack of menstruation. We have already covered this issue in Part 5 of this series. But during her rehabilitation trial in 1456 it was mentioned a few times. So her squire, Jean d’Aulon, testified that:

“I’ve heard it said by many women, who saw the Maid undressed many times and knew her secrets, that she never suffered from the secret illness of women and that no one could ever notice or learn anything of it from her clothes or in any other way”.

The fact alone that it was mentioned during her “rehabilitation” trial signifies that a great weight was put on this one point. And not only then, in the XVth century. Even much later, closer to modernity it still continued to play its role, at least in some circles. In 1822 we read in the “Almanach de Gotha” that:

“Finally, there is the added, remarkable peculiarity, which makes manifest the plans God entertained for her. Womanly in modesty, but exempt, by a particular design, from the weakness of her sex, she was also not subjected to those periodic and inconvenient dues, which, even more than law and custom, prevent women in general fulfilling the functions that men have taken over.”

“Finally, there is the added, remarkable peculiarity, which makes manifest the plans God entertained for her. Womanly in modesty, but exempt, by a particular design, from the weakness of her sex, she was also not subjected to those periodic and inconvenient dues, which, even more than law and custom, prevent women in general fulfilling the functions that men have taken over.”

And 22 years later Jules Michelet continued this particular apologia:

“One thing they (her neighbours) did not know: that in her the life of the spirit dominated, absorbed the lower life, and held in check its vulgar infirmities. Body and soul, she was granted the heavenly grace of remaining a child. She grew up to be robust and handsome; but the physical curse of women never affected her. This was spared her, to the benefit of religious thought and inspiration. Born in the shadow of the church, lulled by the canticle of the bells, fed on legends, she was a legend herself, swift and pure, from her birth to her death.”

(Jules Michelet. “Joan of Arc”. Translated, with an introduction by Albert Guérard. Ann Arbor Paperbacks, 2000. Page 9)

Referring to the fact of a repeated physical examination of Jeanne’s virginity and to the weight formerly accorded to it – weight based on views like these quoted above, Marina Warner concludes in her book (“Joan of Arc. The Image of Female Heroism”, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London 1981, page 20):

“The outcome of such tests for virginity depends more on the expectation of the ministers than on the state of the subjects”.

Warner compares physical tests of virginity with other tests, like ordeal by fire or by water to determine if a person was a witch or a criminal. Perhaps, as we would conclude ourselves, her comparisons are overdone and excessive, given that such “ordeals” were unable to determine anything criminal at all while a physical examination of virginity was, at least sometimes, helpful in establishing reality. But the fact remains that such simple examination could have been misleading. After all it is not so easy even nowadays, let alone in the XVth century, when physiology of sexual organs was not known very well. And even a virgin could have had her hymen torn – e.g. a woman regularly riding a horse, especially if she was wearing heavy armour and taking part in military campaigns…

If no penetration of hymen was found, then the person was considered a virgin and virginity could have been considered to have been the will of God.

The ideal of virginity was flourishing at the time of the cult of the Holy Virgin Mary. It was the Virgin who crushed the skull of the Serpent. It was the Virgin who, among others through her purity, was able to secure God’s mercy for people. Hence, already since the beginning of the Christian era, an uncorrupted, pure body of a woman was considered one of the holiest things existing in nature.

Therefore being a virgin (in French: “Pucelle”) was additionally equipping Joan with the aura of righteousness of her mission.

Marina Warner is supplementing her discourse on virginity with an attempt to trace the origins of the term “Pucelle”. She had to admit however that the origins are not certain. It might be that it derives from “pulchra” (“pulcra”) being Latin for “beautiful” which could have been, with the time passing, changed into “pulcella” which was sometimes used as reference to young girls. The Latin term for a virgin or young girl is however “puella”.

But the meaning of “pucelle” as a term denoting sexual purity was strengthened in the Middle Ages when, in the XIIth century, a new term was introduced, namely “despulceler”, that is “to deflower”.

The role of prophecy in medieval narrative

There was a widespread belief in various prophecies in the Middle Ages. This faith was so rampant that whenever any strong and outstanding personality appeared, there were always some who tried to find out if there was any particular prophecy about the person – which of course means: whether there was any prophecy that could have been made fitting the person in question.

It was believed in the Middle Ages that God personally intervened in human affairs and changed history. The motif of divine intervention was present everywhere in the Old and New Testament. There were the prophets and holy people to whom God spoke directly, giving them specific tasks. And not only spiritual tasks but also political and military ones. In the New Testament no political or military tasks are recorded but, after all, the Christian church included the whole of the Old Testament into the Christian Bible, hence the idea of divine intervention was no stranger to the medieval people.

During Joan’s rehabilitation trial in 1456 a number of prophecies were quoted as confirmations of the divine mission of Joan of Arc. And they were specifically re-made to fit Joan. Those who were supposedly foretelling Joan’s exploits, were:

Merlin

Sybille (Sybil)

Bede

Marie d’Avignon

Engelida

In 1456 during the rehabilitation trial a doctor of law named Jean Barbin testified that during Joan’s examination in Poitiers another master referred to one particular prophecy made supposedly by a woman called “la gasque d’Avignon”:

“In the course of these deliberations Maitre Jean Erault stated that he had heard it said by Marie d’Avignon, who had formerly come to the King, that she had told him that the kingdom of France had much to suffer and many calamities to bear: saying moreover that she had had many visions touching the desolation of the kingdom of France, and amongst others that she had seen much armor which had been presented to her; and that she was alarmed, greatly fearing that she should be forced to take it; but it had been said to her that she need fear nothing, that this armor was not for her, but that a maiden who should come afterwards would bear these arms and deliver the kingdom of France from the enemy. And he believed firmly that Jeanne was the maiden of whom Marie d’Avignon thus spoke”.

There is a problem with this story however: prophecies and visions by Marie d’Avignon had been published in 12 volumes and the above story does not appear in any of them. Merlin of course is a mythical personality, there is no tangible evidence that he himself existed.

As for Bede, the English monk who lived in the VII and VIII century (also known as “Saint Bede” or “Venerable Bede”), his “prophecy” is not in his own original works. It was written in Paris after Joan’s appearance on the political and military stage of the war in France, namely in 1429!

Engelida, “the daughter of the King of Hungary” was supposed to have uttered another prophecy about Joan of Arc, but it was in fact fabricated some time between 17 July 1429 (coronation of Charles VII in Reims) and 8 September 1429 (Joan’s failure to take Paris by force of arms).

In 1429/1430 Christina de Pizan wrote her famous poem on Joan of Arc, the “Ditié de Jeanne d’Arc”. In it she compared Jeanne to all other holy women, including those from the Bible, elevating her above all of them:

Esther, Judith and Deborah

for great virtues they are famed

God’s chosen people through them were saved

from their peril; and I heard

of other many women who

through His divine and mighty aid

performed great many miracles too

But he has done more through this one Maid (stanza 28)

Original in French :

Hester, Judith et Delbora,

Qui furent dames de grant pris,

Par lesqueles Dieu restora

Son pueple, qui fort estoit pris,

Et d’autres plusers ay apris

Qui furent preuses, n’y ot celle,

Mains miracles en a pourpris.

Plus a fait par ceste Pucelle.

And further she claimed that Jeanne’s coming was foreseen by Merlin, Bede and Sibyl:

Merlin, the Sybil and Bede

saw it 500 years ago:

a remedy coming to France’s woe

through her spirit and her feat;

that she would carry the French war banner

And they moreover prophesied

the whole of her action’s manner

All this they long ago described. (stanza 31)

Original in French :

Car Merlin et Sebile et Bede,

Plus de Vc ans a la virent

En esperit, et pour remede

En France en leurs escripz la mirent,

Et leur[s] prophecies en firent,

Disans qu’el pourteroit baniere

Es guerres françoises, et dirent

De son fait toute la maniere.

Sibyl, whose name comes from the Greek σίβυλλα (sibylla), meaning a “prophetess”, was a prophetess and visionary, first depicted by Heraclitus in 5th century BC. There were many Sibyls known in Greek mythology.

So, as we see, there were no prophecies about Jeanne d’Arc at all. All references to such prophecies were merely invented once Jeanne made her sudden entry on the political stage. The only thing that could be done was to re-word some earlier “prophecies” to make them fit her.

In some modern sources, especially on the net, the name of Jeanne is sometimes given as “Jeanne Sybille d’Arc”. Is it her real name? Rather unlikely since she never called herself so. It might be simply a later invention to remind everybody either that she was “foreseen” by visionaries or that she was herself a “visionary”. But it can also be combined with the fact that one of her Godmothers had the name “Sibille” – this name Jeanne mentioned on 21 February 1431(1430 by the old calendar) during her first public interrogation of her condemnation trial:

“Asked who were her Godparents, said one of her mothers was named Agnes, another Jeanne, another Sibille…”

(“Interrogée qui furent ses parrains et marraines, dit qu’une de ses marraines était nommée Agnès, une autre Jeanne, une autre Sibille…”.

In Latin: “Interrogata qui fuerunt ejus patrini et matrinæ : dicit quod una matrinarum vocabatur Agnes, altera Johanna, altera Sibilla…”)

During the rehabilitation trial a testimony by one of the witnesses, Durand Laxart, noted that:

”she told the witness she wished to go to France, to the Dauphin, to have him crowned, declaring : ‘was it not foretold formerly that France should be destroyed by a woman and restored by a maid ?’”

A very similar story was told by another witness, Catherine Le Royer, who was apparently asked by Jeanne:

“Do you not know the prophecy which says that France, lost by a woman, shall be saved by a maid from the marshes of Loraine?”

It is therefore surprising that Jeanne herself did not try to refer to any prophecies in 1431, during her inquisitorial trial in Rouen, in order to seek support in them. The transcript of her interrogation on the 24th March says this:

“She said there was a wood called an oakwood (Bois Chenu) which could be seen from the door of her father’s house ; it is not more than half-a-league away. She does not know and has never heard if the fairies appeared there; but she heard from her brother that it was said in the area that Joan received her mission at the Fairies’ Tree. That was not the case and she told him the contrary. And when she came before her King, several people asked her if there was a wood in her country called Bois Chesnu because there were prophecies which said that from the area of that wood would come a maid who should do marvelous things; but this Jeanne said she put no faith in this.”

The role of religious imagination and practices in her story

According to the official story Jeanne d’Arc was a shepherdess. She never confirmed it herself and during her condemnation trial she even expressed herself in a way that could well be considered a denial of this story. Nevertheless this was the way she was sometimes talked about. Also her successor, the poor Guillaume, was referred to as “Guillaume The Shepherd”. In the Old Testament the future King David was also a shepherd. Christ himself was (and still is) often referred to as “The Good Shepherd”. Shepherds were often depicted as individuals who either carry out certain tasks or are at least present as first and important witnesses – remember the shepherds witnessing the Glory of the newly born Christ?

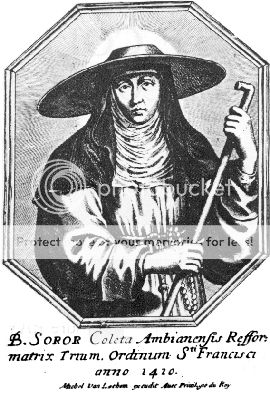

The similarity of an “image” of a person to a very well known saint was most certainly also not without importance. So Jeanne had to bring a small newborn baby back to life – if only for a little while, just enough for it to be baptized. Colette de Corbie – Jeanne’s supposed Franciscan “alter ego” and mentor – had to heal a leper or cure another woman, who had ulcers on her face, by filling her own mouth with water and then blowing (virtually spitting) that water over the sick woman’s face…

It is also interesting that both in the case of Jeanne and Colette it has been maintained that they did not menstruate, which was supposed to be a special grace not heard of in others…

When we point to a miracle as an important element of an image of a person, we have to ask ourselves where the need for a miracle as a “proof” was coming from. It was coming directly from medieval morality and from the attitude to reality. The reality was formed by God. Hence, God was communicating his will and his designs to people among others through miracles. The miracle itself was therefore perceived as a proof of God’s desire. Therefore when papacy decided, in the XII century, to grant itself the exclusive right to canonization of saints, it required a miracle as a proof confirming the correctness of every canonization.

Miracles were not an exclusive attribute of people already canonized but could happen to others just as well, especially to heroes. However, it was the Church’s authority which determined whether the miracle was authentic or not. Hence, there was the argument of proof through a miracle and proof through authority.

One of the charges against Jeanne d’Arc in Rouen was that she had not consulted her “visions” and “voices” with any priest or bishop. We are aware, however, that the charge itself was relatively weak given Jeanne’s examination by clerics and theologians in Poitiers and, namely, an examination lasting about three weeks…

Religion at that time was largely a “religion of habits”. As Isnard Wilhelm Frank sums it up, perhaps too harshly after all:

“With their primitive and archaic religious sense, people found it difficult to cope with the reality of a relationship between human beings and God based on grace, which was difficult to grasp intellectually. They wanted more tangible forms of mediation to which heavenly grace attached itself: in other words, sacred things which were not possessed by demons. The demons were driven out of whatever mediated holiness in the cult by exorcism, and power of heavenly blessing was called down in benedictions.”

(“A History of the Medieval Church”, London 1995, p. 15-16. First editions as “Kirchengeschichte des Mittelalters“, Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 1984 & 1990)

This would also be the reason for which people preferred a “religion of habits” based on rituals, like “ritual purgation of sins” as something tangible and “concrete” which is also widespread today.

Jeanne initially tried to introduce the good habits as she had known them. So, for example, she used the imagery of popular piety during her campaign. These included, among others, sprinkling her banner and pennons with Holy Water to have them blessed for the good cause. This is something which she indirectly confirmed during her trial and we will look at it in the next chapter.

But further to sprinkling water: On 3 March 1431(30) she was asked the following question:

“Jeanne was then asked what she did in the trenches of La Charite: replied that she did make an assault, and said she neither sprinkled nor made anyone sprinkle Holy Water by way of aspersion.”

As it is evident, she was not asked about any Holy Water or sprinkling… Either, then, sprinkling actually took place or she was being sarcastic in her reaction, having been asked about Holy Water earlier on that day… And on that day the interrogation was particularly lengthy…

She was acting as a Godmother. And she was asked about it:

“…, replied that in Troyes once, but at Reims, she has no memory of it, nor at Château-Thierry; she did it twice at Saint-Denis-en-France. And willingly gave sons the name of Charles, for the honor of her king and to girls she gave the name Jeanne, and at other times she gave names as mothers wanted.”

We see her making, especially initially, broad use of religious practices. The “Chronique de La Pucelle” tells us in chapter 44 that while in Blois, assembling her army for Orleans, she gave an order that anyone joining the army must go to confession. Then, already in Orleans, as the “Chronique” continues (chapter 46), after every victory celebrations were held in the city’s churches:

“Thereafter, the Maid, the great lords and their men returned to Orleans and instantly thanks and praise to God were made in all churches by hymns and devotional prayers to the sound of bells, the English could hear them well, being, by this time, very much reduced in power and courage”

“Thereafter, the Maid, the great lords and their men returned to Orleans and instantly thanks and praise to God were made in all churches by hymns and devotional prayers to the sound of bells, the English could hear them well, being, by this time, very much reduced in power and courage”

Later, when the siege was over and the English lined up in an orderly formation, as if ready for a final battle, similar rituals were performed (chapter 49 of the “Chronique”):

“When the English were still in sight, the Maid brought priests wearing their vestments to the field, they sang hymns with great solemnity, responses, and devout prayer, giving thanks and praise to God. She ordered a table and a marble (as an altar) to say two Masses. While the Masses were being said, she asked, ‘Now, look if they (the English) have faces turned away from us or towards us?’ They told her they were going and had their backs turned on them. To which she replied: ‘Let them go, The Lord does not want us to fight them now, you will have another time.’”

This kind of celebration became, with time passing, rarer and rarer. Jeanne was changing. Even Jules Michelet observed in the XIX century:

“War, saintliness, two contradictory terms; it seems that saintliness is the very opposite of war, that it implies charity and peace. But how could a young and valiant heart be engaged in warfare without yielding to the bloodthirsty intoxication of combat and victory?… She had said at the outset that she would never use her sword to kill. Later on she spoke with complacency of the sword she carried at Compiegne, ‘Excellent’, she said, ‘both to thrust and cut’. Does not this mark a change? The holy Maid was turning into a captain. The duke of Alencon said that she showed singular aptitude in the handling of the modern weapon, the most murderous artillery. As the leader of fractious soldiers, constantly grieved and offended by their disorderly conduct, she was becoming harsh and prompt to anger, at least in her effort to curb them.”

In the Middle Ages fasting was prescribed only for the greatest religious feasts but indeed there were plenty of reasons for it almost everyday. This was in part a result of the fact that every day of the official liturgical calendar was a feast. It could be a major feast like Easter, Christmas or Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, but the calendar was full of Saints whose lives could be celebrated.

Caroline Walker – Byman has analyzed the question of importance of food in religious practices in her book “Holy Feast and Holy Host. The religious significance of food to medieval women” (USA, 1987). She notes that fasting was seen as a useful tool also for reasons other than the liturgical calendar:

“Abstinence is seen as a useful tool for conquering lust and, in one case, for converting or defeating heretics” (p. 46). Some other instances “see fasting as inducing miracles or connect holiness and food multiplication”.

We shall study this phenomenon of fasting and food closer as we are aware that Joan’s modest ways of the use of food had earned her a suspicion of having suffered from Anorexia Nervosa. We have touched on this subject before. Now we will look at it again, this time from a purely religious point of view, by taking an effort to re-create its broader background and context.

Food asceticism was, especially for women, also an “imitation of the cross”. In fact women were, more than men, inclined to asceticism, including food asceticism, for religious reasons. Caroline Walker-Byman quotes a number of other researchers, whose studies show this tendency (5). Saint Colette de Corbie, who we mentioned earlier and who Jeanne could have met, was reportedly able to go for a long time without sleeping or eating. Someone even stated that “she went beyond the Fathers” (of the Church) as she could live for 40 days and nights without eating or drinking anything. This tale seems to be grossly exaggerated, of course, as Colette herself never wrote anything of the kind; she merely stressed the importance of fasting. Some stories about Saint Colette say that in her mystical trances she saw herself as “becoming” food. She was to see herself as the tortured flesh of Christ’s body to be offered for other people’s sins.

Was Jeanne trying, as a mystic, to “feed” others spiritually to give them strength?

She had a rather modest appetite. She was fasting on Fridays, apparently eating only several pieces of bread dipped in wine mixed with water. This, itself, bears close resemblance to the Last Supper and to the Christian liturgy. But let us be clear: a phrase “only several pieces of bread…” does not tell us much. What does it mean: “only”? That “only” so little or “only” bread, wine and water and nothing else? How many is “several”? Two or nine? How big is a “piece”? Like a crumb or like a whole slice? What does it tell us about its size or weight? And furthermore: what was then happening to the wine and water in which the bread was dipped? Was it disposed of or consumed as well? Particularly in case of the only meal on a prescribed feast day which commemorates the death of Christ and which by its composition (bread-wine-water) resembles the Eucharist – would the wine and water from such a meal be disposed of? Rather than that, consumption would be a definitely more plausible answer. It is also imaginable that the references to Jeanne’s fasting habits might have these three elements (bread-wine-water) as a focus, more so than mere quantity of food which they offer.

We find a hint at Jeanne’s fasting in the testimony of Jean de Dunois, the “Bastard of Orleans” in the transcript of the rehabilitation trial. Dunois, describing what happened on the day when the Tourelles of Orleans were taken by the French, stated:

“Jeanne was taken to her house, to receive the care which her wound required. When the surgeon had dressed it, she began to eat, contenting herself with four or five slices of bread dipped in wine mixed with a large quantity of water, without, on that day, having eaten or drunk anything else.”

“…et Jeanne fut conduite à son logement pour que sa blessure reçût des soins. Une fois les soins donnés par un chirurgien, elle se restaura en prenant quatre ou cinq rôties dans du vin, coupé de beaucoup d’eau, et elle ne prit aucune autre nourriture ou boisson de tout le jour. ».

« Fuitque ipsa Iohanna ducta ad hospicium suum, ut prepararetur vulnus eius. Qua preparacione facta per cirurgicum, ipsa cepit refectionem suam, sumendo quatuor vel quinque vipas in vino mixto multa aqua, nec alium cibum aut potum sumpsit pro toto die”.

The 7 May in the year 1429 fell on a Saturday. It was not Friday then, the usual day of fasting, so Jeanne indeed did not eat a lot, if we have to believe the Bastard of Orleans. But we have to remember that on that day the Tourelles were taken and the battle raged for the whole day, from 7 a.m. till 8 p.m. We know, however, that on that day Jeanne did not intend to fast. To the home of Orleans’ treasurer, Jacques Boucher, Jeanne’s host, someone brought a fish, an alose or sea-trout, in the morning. The host proposed: “Jeanne, let us eat this fish before you go out”. She however replied: “En nom Dieu (In the name of God), we will not eat it until supper, when we have re-crossed the bridge and have brought back a Godon who will eat his share”. So, there was supposed to be a feast but only after the battle. In the course of the day’s struggle something happened which took her appetite away from her: towards midday Jeanne was seriously wounded by an arrow just above her left breast.

But still four or five slices of bread for supper were not bad for someone wounded in battle.

We have to consider all these aspects because the term “fasting” did not have just one interpretation. We have to remember that initially fasting was supposed to terminate at Vespers. Later (by the XIII century) it terminated at None (which is the “ninth hour of the day”, i.e. 3 pm), by the XIVth century it terminated at noon and a small evening meal was permitted. Fasting was also understood simply as abstinence from meat. However, food for the day could include milk or eggs. Fish, at the same time, included also whales, dolphins or even beavers’ tails or geese. And, while on one hand the religious were leaders at fasting, some of them on the other hand considered a feast day as a “day of feasting”. Given the variety of alternative food, as Caroline Walker Bynam notes:

“The food in some Benedictine monasteries became very lavish. Whereas the average twelfth – or thirteenth-century aristocrat ate meals of four to five courses, some black monks enjoyed as many as thirteen to sixteen courses on major feast days.”

Later, while imprisoned, Jeanne most certainly observed fast during Lent. On 27 February 1430(31) she was asked about it:

“Asked if she would fast every day of Lent, answered:

– Is it in your trial? (- Cella est il de vostre procez?)

And as we told her it was in her trial, said:

– Yes, really, I always fasted during Lent. (- Ouy, vrayement, j’ai tousiours jeuné.)”

This is supported by a statement she made 3 days earlier:

Then by our order, she was interrogated by the distinguished doctor master Jean Beaupère, named above, who first asked her how long it was she had eaten and drunk for the last time. She replied: ‘Since yesterday afternoon’ ( ‘Depuis hier, apprez mydy’)“.

Theological justification, heresy and “theological correctness” (TC)

We have to remember that the Inquisitors at that time were not coming to their trials empty-handed. Already, since the time of the so-called Cathar “heresy” in the XIII century the more experienced inquisitors were writing whole books, virtually handbooks for future inquisitors. Drawing from their own vast experience as well as from earlier cases known to them from similar literature, the authors of those handbooks were warning inquisitors against visions and visionaries.

When Jeanne was asked about the character of her visions, she was responding that she did not think that she could receive her visions while being in the state of sin. Hence, the accusation of heresy. The University of Paris, as we will explain, spoke decidedly against Jeanne. The theologians of the University, among others, stressed that:

“This woman sins when she says she is certain of being received into Paradise as if she were already a partaker of that blessed glory, seeing that on this earthly journey no pilgrim knows if he is worthy of glory or punishment, which the Sovereign Judge alone can tell.”

Jeanne was suspected of a sort of freethinking, similar to the one that existed in the previous century in Flanders and Germany. We shall dwell on this aspect longer in our chapter on similarities between Jeanne and other known religious personages of her era. The freethinking was often associated with the movement of the Free Spirit and its main crime was the conviction of an inborn purity and sinlessness. This is why the judges in Rouen were trying their best to maneuver her into admission of sinlessness.

The answers which Jeanne was often giving confirm that she was not a person who would unconditionally submit herself to the authority of the Church. This fact itself could have given a reason for her to be sentenced. Even after 25 years and after the political climate in France changed completely when Charles VII had taken the whole country back into his hands, some of the former accusers and judges of Jeanne did not completely change their minds regarding her supposed heresy. So for example the canon from Rouen, Thomas de Courcelles, testified in 1456:

“… I never held Jeanne to be a heretic, except in that she obstinately maintained she ought not to submit to the Church; and finally – as my conscience can bear me witness, before God – it seems to me that my words were: ‘Jeanne is now what she was. If she was heretic then, she is so now’. Yet I never positively gave an opinion that she was a heretic. I may add that in the first deliberations there was much discussion and difficulty among those consulted as to whether Jeanne should be reputed a heretic. I never gave an opinion as to her being put to the torture”

It is interesting to note, by the way, how reversed his own opinion had become, given the fact that the original minute of the condemnation trial says very clearly that de Courcelles was in fact in favor of submitting Jeanne to torture…

Sometimes she was confounded as it is shown in the example of the matter of her opinion on who the true pope was at that time. When she was asked about it, she tried to evade the question:

“Asked what she had to say concerning our Holy Father the Pope, and which she believes to be the true pope, replied by asking if there were two of them.”

She was therefore reminded of her earlier (1429) exchange of letters with the Count d’Armagnac who once asked her who of the three popes of that time was the true pope. In her own letter written in reply to the Count she stated that she was unable to assist him immediately with an answer:

“This thing I cannot tell you truly at present, until I am at rest in Paris or elsewhere; for I am now too much hindered by affairs of war; but when you hear that I am in Paris, send a message to me and I will inform you in truth whom you should believe, and what I shall know by the counsel of my Righteous and Sovereign Lord, the King of all the world, and of what you should do to the extent of my power”.

Pressed on this issue by her judges on 1 March 1431(30), she finally stated that in her opinion the true pope was the one residing in Rome (“And as for her, she believes in our Holy Father the Pope in Rome”).

The judges would however not let her get away. They pressed further, asking why then she had to wait till she went somewhere else to give the Count the answer and why she did not tell him straight away that the true pope was the one in Rome. Her answer to this question was quite strange, to say the least:

“…responded that the answer she gave concerned other things than the matter of the three sovereign Pontiffs” (sic!)

Still not satisfied, the judges pressed further:

“Asked if she had said that on the matter of the three sovereign Pontiffs she would have counsel, answered that she never wrote nor gave command to write about the matter of the three sovereign Pontiffs. This she testified upon oath that she had never written nor commanded to write.”

This last statement contradicts somehow her earlier words from the letter to the Count d’Armagnac. (6)

To her credit we must admit that it was not necessarily easy to answer directly who the right pope was at that time.

Even the question of Jeanne’s attire was a question determined by religious Orthodoxy. We have already pointed out at an earlier date that during her trial Jeanne was questioned about this matter, even more frequently than about her willingness to submit to the authority of the Church, including the pope. The Old Testament states:

“The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman’s garment; for all that do so are abomination unto the Lord thy God” (Deuteronomy 22;5)

The accusation of sorcery was another point which surfaced during the trial in Rouen. It was a point very popular with inquisitors of the day as sorcery was very often suspected. Even outside the circles of the Inquisition whole legends circulated about those members of aristocratic families who were believed to have been involved in sorcery and necromancy. And so from among those involved in the struggle for the throne in France we could mention John The Fearless of Burgundy who was murdered in 1419. After he was assassinated, his right hand was cut off “just in case” as he was widely believed to have been an apt sorcerer. The Duke of Orleans, Louis I, who was murdered 12 years earlier, had his hand cut off as well and for the very same reason.

As for Jeanne d’Arc, she was once even asked by her judges where she was keeping her mandrake. Mandrake (Mandragora) is a plant which used to be considered both an aphrodisiac and demoniac. In the Old Testament it is mentioned in the book of Genesis and in the Song of Songs. The Hebrew term “dudaim” meaning “love-plant” was translated into “mandrake” both in the Greek version of the Old Testament (the so-called “Septuagint”) as well as in the Latin translation known as “Vulgate”. If the root of the plant was dug out, it was believed to have been able to scream so that a person hearing the scream would either die or lose his mind. It is believed that the origin of the Latin name “Mandragora” lies in the combination of “man-dragon” (“mas”, “humanus”, “draco”). The root had been used in some magic rituals and if consumed it has hallucinogenic effects. Therefore it was often associated with sorcery. Hence the question Jeanne was asked during her trial.

In religious matters it was very easy to see one and the same expression of faith as “virtuous” or “sinful”, as “pious” or “blasphemous” and “idolatrous” according to the will and wish of an inquisitor. All of those expressions could be interpreted in two extreme and opposite ways, either to the advantage or disadvantage of a defendant. No wonder, then, that Jeanne, being aware of it, might have tried to deny many things which she could have done – we always have to keep this in mind.

Let us have a look at one example from her trial, the one regarding the sprinkling of her pennons with Holy Water. On 3 March 1431(30) she was asked whether they were sprinkled before they were taken to battle for the first time:

“…responded: ‘I do not know, and if it was done, it was not by my command’”

She was then asked whether she had seen them sprinkled with Holy Water. Her answer is interesting:

“This is not in your case. And if I saw them sprinkled, I am advised not to answer about it”.

We believe the “advice” came from her “voices”. And in our view she thus confirmed that the sprinkling had indeed taken place.

Another example was discussed on the same day:

“Asked if the good women of the town did not touch with their rings the ring she wore, responded:

– Many women have touched my hands and rings, but I do not know their thoughts and intentions.”

Earlier on the same day (as we will see in the next chapter) she said that “little could she help” when women “kissed her hands”. But it seems rather unlikely that she had no idea what they thought and felt…

Also Jeanne’s description of saints who visited her smacked of heresy, according to her judges’ perceptions at least. About one year before her trial, another woman called Pieronne was sentenced to death by Inquisition and burned alive in Paris (1430).

“She affirmed and swore that God often appeared to her in human form and talked to her as one friend does to another; that the last time she had seen him he was wearing a long white robe and a red one underneath, which is blasphemous. She would not take back her assertions that she frequently saw God dressed like this.” (“Chronicle of the Citizen of Paris”)

She was, like Jeanne, asserting that “what she did was well done and was God’s will”.

Article 11 of the final 12 articles of accusation of Jeanne in Rouen stated that (examples of dates when she made particular assertions are in brackets):

“This woman did say and confess that to the Voices and the Spirits now under consideration, whom she calls Michael, Gabriel, Catherine and Margaret, she did often do reverence (12 March 1431), uncovering, bending the knee, kissing the earth on which they walk (12 March 1431), vowing to them her virginity (12 March), at times kissing and embracing Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret (17 March); she had touched them with her own hands, corporeally and physically (17 March 1431)…”

Jeanne told her judges a really perplexing story about the alleged “sign” she gave her King as a confirmation of her divine mission. It was a long story about an angel who, accompanied by other angels, appeared to her and to her King. In the footnote (7) we are giving the full account of it from the minutes of the trial under the date 13 March 1431(30). Her judges did not believe this story and we also do not. But it shows nevertheless that Jeanne ventured into such inventions during a very dangerous trial in order to defend her position.

In article 63 of the initial articles of accusation the judges concluded: “Jeanne is not afraid to lie in court, and to violate her own oath when on the subject of her revelations; she did affirm a number of contradictory things, and which imply contradiction among themselves…”

To conclude, we will use yet another of the initial articles of accusation, article 60, which pretty well sums it all up:

“In contempt of the laws and sanctions of the Church, Jeanne had several times before this tribunal refused to speak the truth: by this, she did render suspect all she had said or done in matters of faith and revelation, because she dares not reveal them to ecclesiastical judges; she dreads the just punishment she had merited and of which she appears herself to be conscious, when, on this question, she did in court urge this proverb, that “for speaking the truth, one was often hanged”. Also she had often said: “You will not know all”, and again, “I would rather have my head cut off than tell you all”.”

We have to admit that, except of course of the mention of the “just punishment”, the ecclesiasts in Rouen had put it together correctly and succinctly.

One of the methods used in inquisitions was the application or threat of torture. On 9 May 1431 Jeanne was openly threatened with this “tool”. We must admit that we deeply admire the way she responded to the threat. Here is the account from the minutes of the trial:

“Jeanne was admonished and required to answer the truth about numerous and diverse points contained in her trial to which she refused to reply so far or answered untruthfully albeit we have established them through information most authoritative, proofs and with grave presumptions. Many of these points were read and shown to her, and she was told that if she did not confess the truth about them, she would be put to torture, the instruments of which were shown to her in the tower. And there were also men of our office present, who by Our order, were ready to apply torture in order to bring the way of truth and knowledge and thus could give her the salvation of her soul and her body, which she, through her false inventions, exposed to grave perils.

To which the said Jeanne responded in this manner:

“Truly, if you were to tear me limb from limb, and separate soul from body, I will tell you nothing more, and if I were to say anything else, I would always say that you made me say it by force.”

(In French: “Vrayement, se vous me debviez distraire les membres et faire partir l’ame du corps, si ne vous en diray je aultre chose. Et apprez vous disoye, je diroye que le me auriez faict dire par force. ”)

(In Latin : “Veraciter, si vos deberetis mihi facere distrahi membra, et facere animam recedere a corpore, ego tamen non dicam vobis aliud ; et si aliquid de hoc vobis dicerem, postea semper ego dicerem quod per vim mihi fecissetis dicere. ”)

She added that on the Day of the Holy Cross (Thursday, 3 May 1431) she received comfort from St Gabriel whom she recognized by his voice. She stated that she asked her Voices for advice whether she should submit to the Church as the clergy are pressing her hard to submit. Her Voices were supposedly telling her to wait for God’s help. Asked about her story regarding the royal crown being given to the Archbishop of Reims (and which we quoted here in a footnote) and whether she would refer to the said Archbishop, she replied:

“Make him come here and I will hear him speak, and then I will answer you. Nevertheless he dare not say anything to the contrary of what I have said to you about it.”

(“Faictes le y venir, et que je l’oe parler ; et puis je vous respondray. Il ne me oseroit dire le contraire de ce que je vous en ay dit. ”)

The judges wrote in their conclusion :

“But seeing the hardness of his soul, and her ways of responding, We, the Judges, fearing that the torments of torture would profit her little, decided to postpone their application until We receive more comprehensive advice.”

This is what it meant to endeavour to terrify a battle-hardened soldier. Seeing that their threat would not work, the judges decided to abandon it.

Joan as a visionary and a miracle worker?

Authors writing about Jeanne d’Arc display a variety of opinions regarding the “visions” and “voices” which Jeanne was receiving. We can even divide these authors into at least three groups when it comes to this matter. So there are “visionarists”, “hallucinationists” and “inventionists”. What Jeanne’s “voices” and “visions” were will forever remain a secret of her life. Marina Warner would count among the “visionarists” and so would Jules Michelet or Leon Cristiani. One evident example of a “hallucinationist” would without doubt be Edward Lucie-Smith. He consulted works on hallucinations and arrived at a conclusion that Jeanne’s voices and visions “tend to fit a pattern which is quite familiar to twentieth-century doctors, and which is extensively recorded in medical literature.”

The first appearance of such hallucinations is perceived by subjects “as inexplicable, and as something foreign to the subject’s own concept of himself or herself”. Lucie-Smith sees a similarity to Jeanne’s own words as to how the apparitions came to her. One such example is, in his view, her first “meeting” with St Michael:

“The first time, she was in great doubt if it was St Michael who came to her, and this first time she was much afraid; and she saw him a number of times before she knew it was St Michael”. (8)

He is also referring to the fact that such symptoms are quite frequent, contrary to the common view (9). Jeanne supposedly told her judges that apparitions came to her, on various occasions, in the form of “great multitudes and in very small dimensions”.

As Edward Lucie-Smith notes, “These descriptions precisely match modern cases, where the subject sees the multitudinous personages of his vision much reduced in volume, but extraordinarily brilliant in hue, as if the shrinkage had led in turn to a condensation of the colours.” (10)

The “inventionists” on the other hand tend to believe that Jeanne’s visions and voices were a product of imagination designed to boost her image in order accomplish the political goal she was pursuing. The list of “inventionist” authors (which is probably not very long initially but is tending to grow) would include Marcel Gay and Roger Senzig, Andre Cherpillod and others.

We could, of course, point to yet another attitude and therefore refer to a whole group of authors as “derobationists” (“evasionists”), from the French term “dérobade” meaning “evasion”. These are the authors who intentionally refuse to take a stance on the “visions” and “voices” of Jeanne d’Arc. Here the list is rather long and includes names like Régine Pernoud, Marie-Véronique Clin, Colette Beaune or Vita Sackville-West. We are inclined to include ourselves in this group. However, we are equally ready to look at evidence provided by any author from whichever group. After all, they can be right – all of them – to a certain degree. We would rather look at all incidents individually. So for example we reject Lucie-Smith’s suggestion that Joan’s reference to “fifty thousand men” at Saint-Pierre-le-Moutier in early November 1429, during her attack on the defended township, was a case of hallucination. To him it was “a woman in a state of fugue, no longer in touch with reality surrounding her” (p.189 of Lucie-Smith’s book). To us however, as we pointed out in part 4, it was a typical example of Jeanne’s shrewdness and stratagem in the face of the enemy.

In 1456 the Batard d’Orleans, that is Jean Count de Dunois, in his eulogy-like testimony during the rehabilitation trial admitted that her predictions based on visions not always represented the truth:

„Although Jeanne sometimes spoke in jest of the affairs of war, and although, to encourage the soldiers, she may have foretold events which were not realized, nevertheless, when she spoke seriously of the war, and of her deeds and her mission, she only affirmed earnestly that she was sent to raise the siege of Orléans, and to succor the oppressed people of that town and the neighboring places, and to conduct the King to Reims that he might be consecrated.”

It clearly shows that Joan was deliberately using “prediction” simply as propaganda to encourage soldiers to fight on.

Generally speaking, Jeanne was displaying relatively strong mistrust of visions and visionaries. An example of this was her attitude to a certain Catherine de La Rochelle (La Rochelle is a harbour-city in western France). Catherine told Jeanne that she was regularly receiving visits with instructions. She was maintaining that a white lady dressed in a golden gown was appearing to her. She allegedly demanded of Catherine to visit various towns and cities of France loyal to Charles VII to encourage people to give her their gold, silver and other valuables. If they did not obey, then Catherine was to see through their life secrets and force them to use their wealth to support Jeanne’s military effort. Jeanne told her simply to go back to her husband and to look after her children. She spent two consecutive nights with Catherine to see the mysterious “white lady” but the lady did not appear. Later Catherine de La Rochelle was taking her revenge on Jeanne. In 1430 she was telling judges in Paris that Jeanne had two advisors who were already visiting her after she was captured and that Jeanne supposedly told them that she would escape from prison with the help of the devil.

As the Middle Ages were full of “prophecies”, “miracles” and predictions, so many expected them also from Jeanne d’Arc. When in March 1430 a small child considered dead woke up for a little moment while she prayed over it, it was considered a miracle. When a frightened horse was calmed after she ordered to lead it towards a cross standing at a church wall, it was considered a miracle. When she was saying that she was afraid of treason and later she was indeed captured, it was considered to be a kind of “vision”, “prediction” or “prophecy” (11). It was also considered a kind of a “prophecy” when she expressed a supposition that she would be wounded by an arrow – especially since soon after she was indeed wounded in that way.

Sometimes she was amused and sometimes irritated by examples of simple piety. When in July 1429 she met the famous mendicant friar Brother Richard and he, to make sure that she was not a witch, made a sign of the Cross and started sprinkling holy water around, she told him “Approach boldly, I shall not fly away” (“Aprochez hardyment. Je ne m’envoleray pas”/ “Appropinquetis audacter, ego non evolabo”) When she was asked by a crowd of women to touch their rosaries, she laughed and told them: “Touch them yourselves, your touch will make them as good as mine.”

In 1456 Simon Beaucroix testified that “Jeanne was very upset and most displeased when some good women came to her and showed her signs of adoration. This annoyed her.”

But at least at this point Beaucroix seems to have been contradicted by Jeanne herself. On the 3 March 1430(31) she was asked about it directly:

“Asked if she did not know the feeling of those of her party when they kissed her feet, hands and clothes, said that many people willingly came to see her, and said they kissed her hands and little she could help . Because poor people willingly came to her because she did nothing wrong to them but helped as much as she could.”

Was Joan a tertiary?

There is a relatively strong notion that Joan of Arc might have been a tertiary, that is, a member of the Third (Secular) Franciscan Order. This is definitely one of those episodes in Joan’s life which we have to include among the possibilities, among the things that could have happened but for which we do not have any proof whatsoever.

There is a strong probability that Joan met yet another woman who is a saint in the Catholic canon: Saint Colette, and more exactly Colette de Corbie. In the first half of November 1429 both Jeanne and Colette were in Moulins. There is no evidence that they ever met. And yet a number of historians and writers who devoted time to research the historic Joan of Arc have pointed to this possibility.

So Vita Sackville-West in her book written in 1936 states:

“It seems more than probable that Jeanne must have come across this very remarkable woman at Moulins in November 1429, and, although there is no evidence to prove their meeting, there is equally none to disprove it. It is almost incredible that these two women, two of the great saints of France, should have been in the same town on the same date – as we know they were – without contriving to meet.” (V. Sackville-West. “Saint Joan of Arc”, New York 2001, p. 247).

The meeting of the two saints in Moulins seems even more likely to have taken place, as there was also – and at the same time – yet another woman, whom Joan and Colette knew very well. She was Marie de Bourbon, a friend of Jeanne and a foundress of Colette’s convent in Moulins. According to local tradition, Jeanne was praying in the chapel of the cloister of the order of St Claire of which Colette was a member.

Colette de Corbie was born on 13 January 1381. In 1399 she joined the Beguines, that is, the movement we mentioned before. And in 1402 she joined the Third Franciscan Order. By 1423 she came to know yet another member of the Third Order, and namely a very powerful lady and an influential member of the French court: Yolande d’Anjou (1384 – 1442). It was Yolande, known as “The Queen of Four Kingdoms” (Sicily, Naples, Jerusalem and Aragon) who was the driving force behind the Dauphin, Charles VII. Her immediate and strong support for Jeanne d’Arc is very well known. It is believed by many authors that it was Yolande who formed Joan of Arc and prepared her for her mission. She was also co-financing Joan’s military efforts. We will touch on this issue at some other time.

And Colette de Corbie could have met Jeanne not just in Moulins but also somewhere else. The French historian Jacques Guérillon seems to have been convinced of such a possibility. In his book “Mais qui est-tu Jeanne d’Arc?” (i.e. “But who are you, Joan of Arc?”), he wrote:

“This same Colette de Corbie, indefatigable traveler, never missed stopping at Domrémy each time her peregrinations brought her to the neighbourhood, and she lodged in the hermitage of the Bois Chenu (i.e. Oakwood) where she convoked her regional of the third Franciscan order that she introduced into the rules and spirit of the order. Among her adepts, Joan (…) received at 18 years of age the grade of Grande Dame Discréte.”

(quoted from: Roger Senzig, Marcel Gay. “L’Affaire Jeanne d’Arc”. Editions Florent Massot, 2007, p. 148).

As we see, Guérillon went quite far in his assumptions… Of course Bois Chenu and Domrémy are the very home of Jeanne d’Arc… There is also a tradition according to which Colette gave Jeanne a ring inscribed “Jesus Maria”.

One more detail can also be interesting to us: Domrémy was also the domain of the French aristocratic family of de Bourlémont. We have read about that particular family before: it was when we mentioned that since 1420 (or even 1419) the d’Arc family was living in a local small castle in Domrémy, the so-called “Chateau de l’Isle” („un château nommé l’Isle”) which was leased from the family de Bourlémont. And incidentally – as if the coincidences just given were still not enough – the family of de Bourlémont happened to be the very family of the mother of Saint Francis of Assisi, the founder of the order…