This chapter is dedicated solely to the issue of the reconstruction of the looks of Jeanne d’Arc. We have been touching this subject extensively in some of our earlier texts, particularly in the following articles:

“Claude, the Second Face of Joan of Arc”

as well as in some parts of our series Secrets of the Life of Joan of Arc, parts 4 (“Her looks, personality and skills” ), 5 (“Her personal affairs” ) and part 6 (“The religious factors” ).

The visual material will be further updated in those texts. However it is here where we will be publishing most of the recent reconstructions, both general reconstructions of her looks and reconstructions of her face.

Her face

As we have mentioned on previous occasions, the visual evidence of Jeanne’s face comes from 3 main sources:

1. The painted facial profile of Jeanne des Armoises from the castle of Jaulny. For our analysis it is quite immaterial if Jeanne des Armoises was Jeanne d’Arc personally, her sister or an impostor. The main point remains that whether or not she was Jeanne d’Arc, she must have been at least very similar to her if so many people were able to accept her as Jeanne d’Arc;

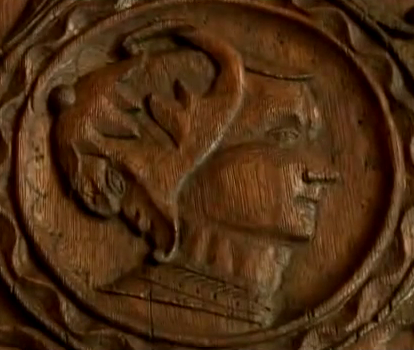

2. The wood-carved version of the same profile from a wooden door from the house in Metz. This door was once in the house owned by Jeanne and Robert des Armoises in Metz. It is a relatively small door, only approximately 1.2 m high, most likely leading into a storage facility of the house. The facial profiles of Jeanne and Robert carved in it are very similar to their painted versions from Jaulny, albeit much more crude in their form. In the case of Jeanne the carved version suggests that in her middle age Jeanne might have been quite corpulent as her cheek strongly suggests. Moreover, the way in which the profile was carved gives an impression of quite prominent cheek-bones.

3. The head of a former statue of St. Maurice from a church in Orleans.

Albeit that St Maurice was a man, and – according to at least some versions of his story – he was also supposed to have been of black African origin, the face of his statue from Orleans clearly shows a young woman and namely white (“Caucasian”, “Aryan”). As the sculpture was in a church located in Orleans and especially since it has been dated as being from the XVth century, there is a general agreement that it was in fact a representation of Jeanne d’Arc. The church was demolished in 1850. Of the statue only the head survives and it is now at the Musée Historique et Archeologique in Orleans. As we can easily see from the photographic images taken from various angles, the head has quite prominent cheek-bones.

We have been trying to reconstruct the face of Jeanne before, the first time using the reconstruction done by Professor Ursula Wittwer-Backofen, then directly from the painting from Jaulny, and ending up with a combination of various photographs available on the internet and transformed to fit into the available evidence of Jeanne’s looks.

The results however were inconclusive. We decided therefore to change the method and started again very recently with the profile from Jaulny and with the head from Orleans. This time however we took a different approach and created what we call “photographizations” of both the painted profile from Jaulny and of the sculpture. We used Photoshop to re-create both images through the application of photographs to see how both faces could have looked in reality if they were photographed. And this is the way we intend to continue our “exercise” of the facial reconstruction of Jeanne d’Arc.

Photos also proved of great value of course in regard to the re-creation of Jeanne’s looks dressed in various kinds of clothing which she could have worn in the XVth century.

In our earlier attempts of facial reconstruction we have handled the prominent eyes of Jeanne from the sculpture of “St Maurice” too lightly. The reason was of course that on this very sculpture the eyes were made all too crudely, like “eyes of a frog”, as we expressed ourselves. Yet we probably have to give some credit to the artist after all. It is true that the artist had problems, which must have obviously resulted from the type of tools available to him.

When we look at the sculpture, no matter from which angle, it looks as if the upper and lower part of the face were made by two completely different people – the lower part created by a better artist, the upper one by someone else, less experienced in his trade. Yet most likely it was one and the same person after all. What is particularly striking is the fact that the convex curves (like the nose, chin and lips) did not present any particular problem to the craftsman, but the concave curves of the eyes (or more exactly of the eyelids between eyebrows and eyeballs) proved too difficult. This makes us believe that it was indeed the tools available which made all the difference. This could have also previously been a problem for artists thousands of years ago, as even the relatively well advanced sculpture of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti confirms. There too the eyelids seem unreal. By the way, the nose of Nefertiti shows clear similarity to the nose from the head from Orleans.

But if the artist from Orleans nevertheless insisted on creating very prominent eyes, there must have been a reason for him to undertake a task so difficult to perform.

On the painted and carved profiles of Jeanne des Armoises her eyes do not seem as prominent as those on the sculpture from Orleans. But then we have to remember that the profiles on the one hand and the sculpture on the other are images of a person of markedly different age: the head shows us a woman of around 20 – 23 years while both profiles are of a woman of at least 40 years of age, a woman who was already somewhat corpulent, so that even very prominent eyes would not have looked so due to the fat within and around the eyelids.

But if we look closer at the eyes on the profiles, they still look like they might have been prominent at a younger age after all. An enlargement of the painting shows it to us clearly – just as it reveals that Jeanne’s eye was in fact blue – which might escape an observer at first glance.

As for the colour of Jeanne’s hair, we have accounts in regard to two different seals attached to her letters. We have written about them in part 4 of our series:

“As if that wasn’t enough, there have survived to modern times (though not to our times, unfortunately,) two hairs, probably of Joan, squeezed in the seals of letters sent by her. One of these letters is a letter to the people of Riom from November 9, 1429. The second letter is the one presented here on another occasion, written on March 16, 1430 to the inhabitants of Reims. The first letter was “discovered” in the archives of Riom in 1884 and described, together with the stamp, by Jules Quicherat. There existed in the Middle Ages a custom, fairly often adhered to, of pressing a hair into the still soft and hot seal of a letter. This custom was used to confirm the authenticity of the wax seal. The seal of the letter from the year 1429 still exists, even with the thumbprint. But the hair has already been lost many years ago (already in 1936, Vita Sackville-West reported its disappearance in her famous biography of Joan). From the letter from 1430 the hair disappeared, however, together with the stamp”.

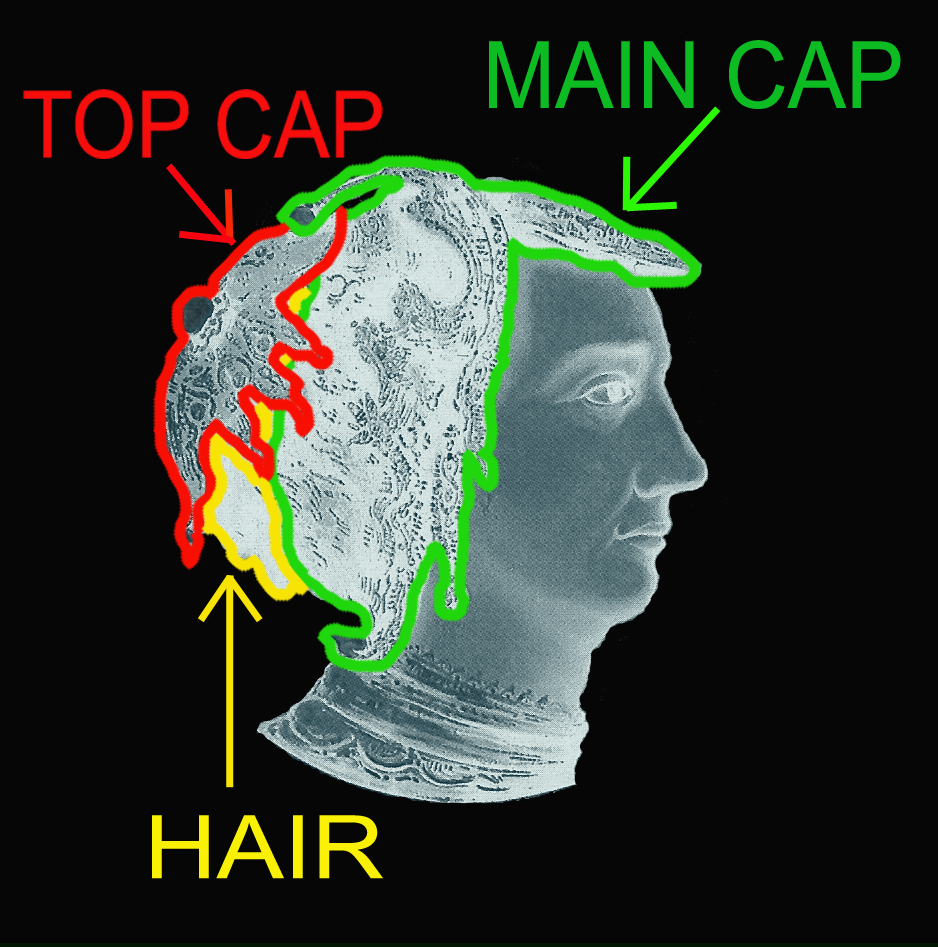

Black hair appears also on the painted profile of Jeanne des Armoises. We had an exchange of opinions with our befriended Researcher from France about this hair – as we had before about Jeanne’s alleged (supposed) pregnancy (see part 5 of our series). Our French friend believes that the portrait from Jaulny, which he had seen on a number of occasions as he is befriended with the owners of the castle, does not show any hair as the hair is completely covered with headgear.

We have to admit that his impression can be – at least to some extent – justified by the fact that the painter who created the portrait did not try to depict the headgear all too clearly, that he instead treated it in an “impressionistic” way, so to speak. And yet the hair can be seen on the left, at the bottom of the headgear.

The style the painter used might be “impressionistic”, yet it clearly shows that the fabric of the cap was thickly covered with golden embroidery. In such a case the fabric itself could not have been thin but much thicker – at least as thick as a good quality velvet or even felt (for our “photographization” we used photos of blue velvet to re-create the image of the headgear). This would have been especially true since golden threads are much heavier than others and in some cases the embroidery consisted not only of threads as such but also of very small pieces of metal or even jewels sewn onto the fabric. As the pattern of the brocade is not clearly shown on the painting, we therefore did not try to reproduce it exactly since we do not know which figures or shapes it represents. Instead we simply used photos of real embroidery (especially in the case of large patterns).

As we can see, the cap fits the head very closely, adheres to the top of the head and to the skin of the face on both sides. It also covers the ears completely and to certain degree also the back side of the neck. As it was more common for a woman to have her head covered in the Middle Ages for most of each day than is the case nowadays, we can easily imagine how uncomfortable it would have been for a woman to wear this kind of cap. The skin of her head would have sweated profusely if the cap consisted only of one part which would not have allowed any access of fresh air to the hair and scalp. And this would have been particularly true in the case of a thick, brocaded fabric. Bearing in mind that the XVth century was not the time of luxury shampoos and conditioners being readily available to the public. Therefore, one to three days of this kind of “torture” to the scalp would have inevitably resulted, among other things, in a bad smell…

Let us have a closer look at the headgear from the original painting. Most obviously it is divided into two parts: the main headwear covering the skull and “hanging” from the hair which is tied at the back, and the upper “skullcap” which covers the hair which was pushed through the main part thus enabling the headwear to hang firmly on it while on the other hand allowing the woman to do her hair comfortably after she had pushed it through the main part of the cap. Moreover this design also allows an unlimited access of air to the skin and hair thus allowing the person maximum comfort.

Let us have a closer look at the headgear from the original painting. Most obviously it is divided into two parts: the main headwear covering the skull and “hanging” from the hair which is tied at the back, and the upper “skullcap” which covers the hair which was pushed through the main part thus enabling the headwear to hang firmly on it while on the other hand allowing the woman to do her hair comfortably after she had pushed it through the main part of the cap. Moreover this design also allows an unlimited access of air to the skin and hair thus allowing the person maximum comfort.

We can clearly conclude that whoever made this particular headwear for Jeanne des Armoises (perhaps some local milliner from Metz?) most certainly knew his trade well – we assume that otherwise his product would not have been accepted by the aristocratic woman, who most obviously must have liked this headwear if she even decided to be painted in it…

Given the results of comparisons between our “photograpfization” of both the painted profile of Jeanne des Armoises (and keeping in mind the hint at cheekbones from the relief from Metz) and of the head from Orleans, we created what we believe might be at least the type of physiognomy which Jeanne d’Arc represented. While creating the face below, we of course remembered the military (knightly) sort of hairstyle which we mentioned quite a few times before throughout our series of articles.

And this is how she would have looked in a suit of armor:

Now in a helmet like on the famous sculpture in Orleans:

Given the fact that a large helmet would cast shadows over the face, the final image could have been like this:

Below we are presenting two different versions of the “Puella Aurelianensis”, the original one (which we introduced here in the article on the religious factors in the life of Jeanne (Part 6 of our series) and the second one with the face taken from the “photographization” of the sculpture from Orleans:

… and the latest one:

Of course we will continue our attempts to reconstruct Jeanne’s looks also in regard to the possible clothing she used to wear.

______________________________

______________________________

A case study

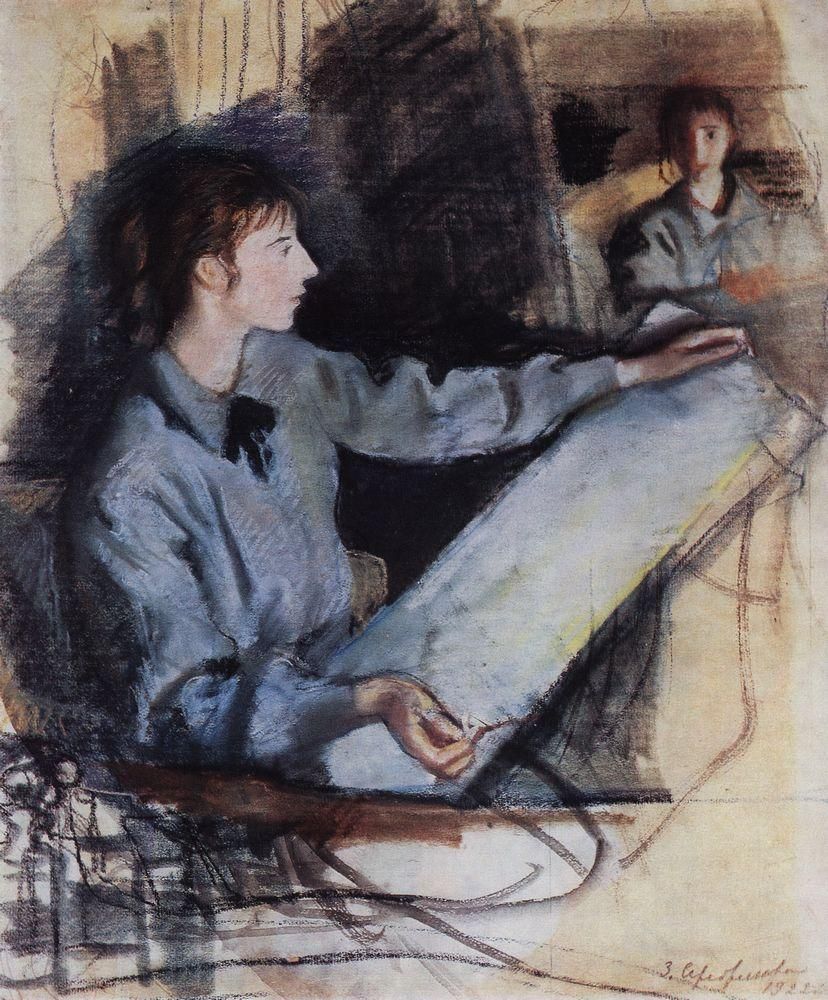

Some time after having finished the first version of this article, I came across this image of a face. It is a watercolour self-portrait by the Russian painter Zinaida Serebriakova (1884 – 1967), who was born in Ukraine and died in Paris. And more specifically it is one of a great many of her self-portraits. The artist painted, drew and sketched virtually dozens of her self-portraits. Thank to this we are now in the position to study her face quite well. She created images of her face both from the front and from various angles.

Some time after having finished the first version of this article, I came across this image of a face. It is a watercolour self-portrait by the Russian painter Zinaida Serebriakova (1884 – 1967), who was born in Ukraine and died in Paris. And more specifically it is one of a great many of her self-portraits. The artist painted, drew and sketched virtually dozens of her self-portraits. Thank to this we are now in the position to study her face quite well. She created images of her face both from the front and from various angles.

What struck us was the fact that the proportions of her face are somewhat reminiscent of the sculpture from Orleans and the portrait of Jeanne des Armoises. Serebriakova’s face seems a bit more slender and had a nose similar to the one of Jeanne des Armoises, perhaps even a bit more prominent. And the artist had dark eyes – while Jeanne had blue eyes.

If Walter Rost was right in regards to the body-build of Jeanne d’Arc, then a relatively slender face could actually fit well into the whole of her figure, the more so because, as we know from the records, Jeanne was not known for a great appetite during her military service, which in itself absorbed a lot of energy from her metabolism.

This would mean that Jeannae’s face would have had a little more sharp features than the face of Zinaida Serebriakova. This factor found its reflection in our presented version of Joan’s facial reconstruction (below).

As it is shown in the series of Serebriakova’s self-portraits, including these two profiles, the painter often used two mirrors so as to provide two images of her face, from the front and a profile, on a single painting.

As it is shown in the series of Serebriakova’s self-portraits, including these two profiles, the painter often used two mirrors so as to provide two images of her face, from the front and a profile, on a single painting.

The profiles shown here illustrate the one thing by which the face of the artist certainly differed from the face of Joan des Armoises and Joan of Arc: Serebriakova’s lower jaw is somehow more “pushed back” compared to the profile of Jeanne.

However, we have, in addition to a variety of painted and drawn portraits of the artist, also something else. Namely, her photograph from the period when she was already nearing her middle age. And when we look at this photograph and compare it with the profile from Jaulny, we see that these two faces looke quite similar to each other. Even the apparent “grimace” in the corner of Serebriakova’s mouth corresponds with the one on the image of Joan des Armoises from the castle in Jaulny…

Thus, the facial features of Serebriakova could even be quite similar to the facial features of Joan of Arc.

Therefore, we made a kind of “amendment” to the previously produced facial reconstruction of Jeanne. So how would Jeanne have looked if she had her face a little bit like Serebriakova’s? Here she is: